Hard on the heels of the law's passage came a gubernatorial election that resulted in the defeat of their favored candidate, Republican James Watson, by Democrat Thomas Marshall. A recovering alcoholic himself, Marshall believed that prohibition was unenforceable and would inevitably create widespread law-breaking. For this reason he advocated the repeal of county-option prohibition, preferring the careful regulation of saloons to correct their worst aspects. The 1910 state congressional election gave him a like-minded Democratic majority in both the House and Senate.

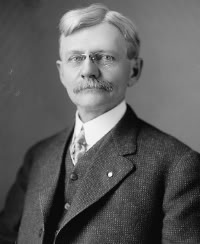

Indiana Governor Thomas R. Marshall

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Out of the various reform proposals, the Democrats fashioned the Proctor bill (named for Senator Robert E. Proctor), and it became law in March 1911.

The Proctor law repealed county option by two means. First, it made the municipality and township the option units, meaning that any town or township could vote itself wet even though it was located in a county that had opted for dryness. Secondly, the bill provided that all counties that had voted themselves dry would become open to saloons two years after the date of that election; thus, any town or township that wanted to stay dry after those two years had to do so by a local election.

On the plus side, from the dry point of view, the Proctor law preserved the Nicholson-Moore remonstrance. It also imposed restrictions on eligibility for a liquor license and on the the operation of saloons. Now, any successful applicant for a license had to be a U.S. citizen or a resident of Indiana for at least ten years, and the owner of his own saloon fixtures as well as the lease on his building (thus eliminating the brewery saloon), with no conviction within the previous four years for any violation of liquor laws. Each applicant could hold only one license.

(While the bill was still under consideration by the legislature, the Gazette had reported that one of its proposals was to tie the number of permissible saloons to local population: one for every 500 people. "This provision," lamented the Gazette, "would permit … only two saloons in Hobart." However, that draconian limit seems not to have been included in the final bill, since we find Hobart, three years later, boasting of ten saloons for a population of 3,500.)

As for the day-to-day operations of saloons, the Proctor law, as filtered through the Board of Commissioners of Lake County, imposed a number of "stringent rulings." A saloonkeeper could lose his liquor license for opening his saloon for business on any Sunday, holiday or election day, or for allowing any of the following in or about his saloon:

- slot machines, or any other form of gambling;

- the presence of "lewd women";

- bartending by any woman, even the saloonkeeper's wife;

- the display of "nude or lascivious pictures";

- rooms above or behind the saloon maintained "for immoral purposes"; or

- the operation of any other business directly in the saloon, including real estate or employment offices, pool rooms or barber shops.

Clearly, since the Proctor law applied to all saloons, it had more effect on Lake County than the county-option law. Whether it specifically affected the Ainsworth saloon, I don't know: since I've read nothing about any action taken against William F. Wollenberg, I suppose that either he had no bartending wife, lewd women, lascivious pictures, slot machines, etc. in the first place, or else he duly removed them … or else — what is also a distinct possibility — the law was not strictly enforced.

Sources:

♦ "County Commissioners Settle License Question." Hobart Gazette 13 Apr. 1911.

♦ Hamelle, W.H. A Standard History of White County. Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1915.

♦ Lantzer, Jason S. "Dark Beverage of Hell": The Transformation of Hamilton County's Dry Crusade, 1876-1936. Conner Prairie Interactive History Park. https://connerprairie.org/ (30 July 2010).

♦ "Hobart Has." Hobart News 23 July 1914.

♦ Lantzer, Jason S. "Prohibition Is Here to Stay": The Reverend Edward S. Shumaker and the Dry Crusade in America. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2009.

♦ "The New Liquor Law." Hobart Gazette 10 Mar. 1911.

♦ "The Proctor Saloon Bill." Hobart Gazette 10 Feb. 1911.

2 comments:

Thanks so much for this article. Researching my great grandfather who was a saloon keeper in 1900s era Brownsburg, Indiana. I was able via news articles to track the ebb and flow of events in regards to liquor and the temperance movement up to the... "relegalization" of saloons in early 1911. Seeing a reference to The Proctor Bill, your page saved me a lot of digging to find more info. Awesome. Thanks so much.

Glad to be useful!

Post a Comment