(Click on image to enlarge)

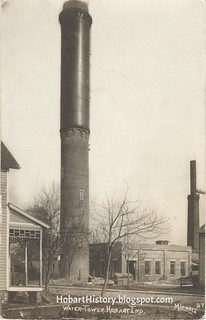

Hobart's electrical power and water plant circa 1912. (Image courtesy of Bonnie.)

Hobart had been producing its own electricity for at least two decades, and its citizens had grown used to its convenience in their homes and businesses, and in their illuminated streets. Newspaper reports suggest that by 1918 the municipal plant on New Street had two engines producing electricity, but during that hard winter one of them "fell to pieces" and was not replaced. Thus for many months Hobart's power depended on a single ten-year-old engine running 24 hours a day. Around midnight on January 6, 1919, that little engine just couldn't take anymore — something wrong with its piston rings, apparently, as they disintegrated during a hasty attempt at repair. No replacement rings were on hand, nor were they easy to get. Plant superintendent Robert Wheaton set about tracking down a source. By early morning he had learned that in Milwaukee were two of the rings his engine needed, the only two rings available in the whole city. He jumped on the first train out of Hobart for a mad dash to Milwaukee.

Fortunately, the town's water supply was provided by a separate steam pump that continued to operate. But there would be no electricity until Superintendent Wheaton got back with those rings and fitted them to the engine.

Hobart awoke that Tuesday morning to a taste of the inconvenience of the good old days. The greatest problem was not in heating homes and businesses (coal stoves and furnaces were abundant) nor even in lighting them (there were probably numerous kerosene lamps still on hand), but in the sudden absence of the machines that people had come to rely on, in homes, stores, factories, lumberyards — everywhere. "Those who use motors for power in various ways were strictly up against it for the time being," the Gazette said. "All machinery was at a standstill. People can get along for a day or so without lights much better than without power. Electricity to operate motors is needed every hour of the day."

An evening train brought Superintendent Wheaton back from Milwaukee, bearing the precious rings. He hurried to the power plant, and there he labored through the night. About 2:00 a.m. Wednesday morning, the old engine fired up again, and brought back the 20th century.

It had been only 24 hours, a minor inconvenience, but it showed a serious problem in relying on a single, aging engine to power the town. Possibly spurred by this episode, before the end of the week Hobart had settled with the town of West Branch, Iowa, for the purchase of that town's power plant engine — no longer needed, now that West Branch was buying electricity rather than manufacturing its own. While August Kegebein* went to West Branch to get the new engine, the newspapers settled down to fighting over the lesson to be drawn from those powerless 24 hours.

In the opinion of the Gazette, Hobart ought to quit trying to manufacture its own power and instead buy it from a large supplier. The large manufacturers were better equipped to supply power reliably. As to the question of cost, the town could buy electricity wholesale to get a good price, then resell it to local homes and businesses (and streetcar lines) at a price that would more than recoup the wholesale cost, while still being cheaper than home-manufactured power. The scheme was quite feasible, the editor pointed out, as there were "two large power lines at our very door."

The next week's News implied that behind such talk were large electricity manufacturers who were just itching to "break into our midst and take over" Hobart's power-plant business. After running at a loss for much of its early history, the town's plant had begun to break even and even turn a profit in recent years, and now that it was recovering from the "lightless nights" and other difficulties of 1918, it naturally became a target for the greed of private power companies.

Were the large suppliers more reliable? Not a bit of it! — to back up this point, the News now had August Kegebein's report from West Branch, Iowa. During the week he had spent there making arrangements to bring back the new engine, he said, the purchased power supply had failed twice — on two separate occasions the town had spent a whole night in darkness. Hobart could probably expect the same thing if it was foolish enough to follow West Branch's example. Moreover, the Calumet Region often had electrical storms, and they were known to cause trouble for long transmission lines.

And Hobart was not the only town in the area to have trouble lately; Valparaiso had gone half a day without power, and Waukegan, Illinois, more than two days. After all those years of largely uninterrupted service in Hobart, a 24-hour power failure no reason to get hysterical.

I believe the viewpoint put forth by the News held sway for many years to come, but we will see.

___________________________

*His first name is not given in any of the newspaper reports. I am guessing at it based on the 1920 census, which shows August Kegebein as an "operator" employed in a "Light & W. Plant."

Sources:

♦ 1920 Census.

♦ "Hobart in Darkness." Hobart Gazette 10 Jan. 1919.

♦ "Hobart's Municipal Light and Water Plant." Hobart News 16 Jan. 1919.

No comments:

Post a Comment