The campaign leading up to the November 1916 election was surprisingly quiet about prohibition. The Republican candidate for governor, James P. Goodrich, refused to take a position on the topic, although he was "a devout Presbyterian with strong ties to the church-based dry cause" and was known to favor temperance; his Democratic opponent, John Adair, likewise avoided the issue. The Prohibition party fielded its own candidate, and the Progressive party candidate was former governor James F. Hanly, who had signed

county-option prohibition into law in 1908; but these latter two were trounced in the election, and Goodrich won a narrow victory over Adair. Even after winning, Goodrich did not take a definite stand on prohibition.

As 1916 neared its close, however, (in the words of a contemporary historian) "a great agitation began to be manifest throughout the state." In December the state's dry forces formed a coalition called the Indiana Dry Federation, which soon came to include the powerful Indiana Anti-Saloon League. With centralized leadership and hard-won political savvy, the Indiana Dry Federation was able to rally intense grass-roots efforts. Petitions and delegates rained down on the state capitol as the 1917 General Assembly convened.

Thanks to dry lobbying, the assembly's first month saw the introduction of the Wright prohibition bill, named for its drafter, Congressmen Frank Wright. A newspaper article described its terms as "drastic" and "written with the intention of making traffic in liquor illegal."

As the proposed bill was under consideration by the legislature, the dry forces stepped up their lobbying efforts. They presented legislators with petitions signed by some 400,000 prohibition advocates. They held rallies in the statehouse daily — sometimes several times a day. This was in addition to demonstrations in other towns and cities, and the "propaganda" in newspapers and other publications across the state. William Jennings Bryan, on a visit to Indianapolis, personally lobbied the governor and the legislature for prohibition.

The Wright bill passed the House with a wide margin of victory — 70 to 28. As the bill went to the Senate, the drys kept up the pressure, with more petitions, more lobbying delegations and more demonstrations.

The day the Senate voted on the bill saw "one of the most stirring scenes ever witnessed at the state capitol," according to a contemporary news article. In spite of bitterly cold temperatures, "[t]housands of prohibition workers crowded the corridors of the capitol building and lined up in the street, awaiting the vote which was to be cast, and would reap the harvest of their efforts…."

On February 2, the Wright bill passed the Senate by a 38-to-11 vote. And a week later Governor Goodrich finally made clear his stance on prohibition when, at a public ceremony and under the unblinking gaze of a motion-picture camera, he signed the bill into law.

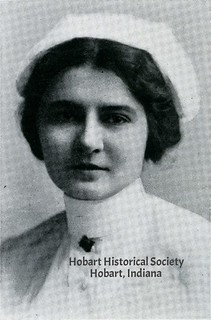

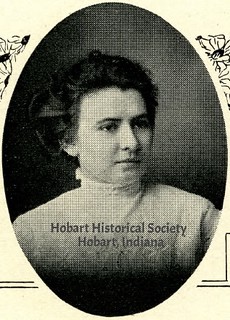

Indiana Governor James P. Goodrich

Indiana Governor James P. Goodrich

(Image credit: Indiana Historical Society.)

The essence of the bill was this:

After the second day of April, 1918, it shall be unlawful for any person to manufacture, sell, barter, exchange, give away, furnish or otherwise dispose of any liquors except as in this act provided.

The few exceptions included the manufacture of wine, cider and other non-spirituous liquids for private, domestic use (you could even serve such drinks to guests in your home, so long as your home really was private, "not used as a public resort of any kind"); sacramental wine; pure grain alcohol used for medical, scientific or industrial purposes; and liquor prescribed by a physician for medical reasons, which could be sold by druggists in small quantities. People already in possession of properly bonded alcohol before the law's effective date could still ship it to states where it was not prohibited.

Violators of the law faced, for their first offense, a fine of $100 to $500 and a jail sentence of 30 days to six months; and for second and later offenses, the minimum fine was raised to $200 and the minimum jail sentence 60 days.

♦ ♦ ♦

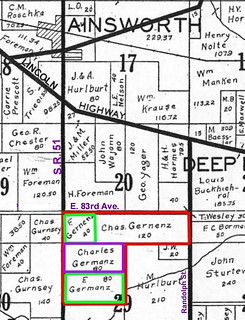

… So, it had finally happened. Back in Ainsworth, in their rooms over the saloon, William and Adelphine Wollenberg must have asked each other, "Now what?" The saloon had supported their family for nearly 10 years. One more year, then Will would have to find a new line of work, and the terra cotta building where the local men had gathered since 1899 to drink and to smoke, to talk and to fight, would have to find a new use.

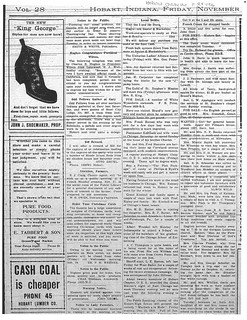

Meanwhile, the

News noted how fitting it was that the well on Charles Borger's Third Street lot, which had supplied the neighborhood with good drinking water for a dozen years — suddenly, mysteriously, dried up. Mr. Borger had to dig a new well.

Sources:

♦ Canup, Charles. "Temperance Movements and Legislation in Indiana." Indiana Magazine of History XVI:1 (March 1920).

♦ "Indiana Dry Bill Is Signed." Hobart Gazette 16 Feb. 1917.

♦ "Indiana To Be Dry April 2, 1918." Hobart Gazette 9 Feb. 1917.

♦ Lantzer, Jason S. "Prohibition Is Here To Stay": The Reverence Edward S. Shumaker and the Dry Crusade in America. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2009.

♦ "Personal and Local Mention." Hobart News 1 Mar. 1917.

♦ "Senate Passes 'Dry' Measure." Hobart News 8 Feb. 1917.