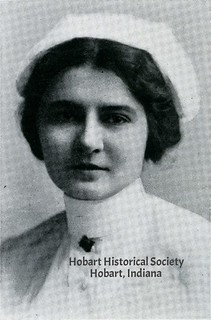

(Click on image to enlarge. Image courtesy of the Hobart Historical Society.)

Emma Gruel in nurse's uniform, circa 1918.

During the last week of December 1916, John and Louise Gruel received a cablegram from Berlin: Christmas greetings from their daughter, Emma. They must have been delighted at this assurance that she was alive and well, since they'd had to take it on faith for most of her time in Germany, communications between Ainsworth and the German Empire being so unreliable. But the cablegram left them puzzled about Emma's immediate future: the six months' term she'd signed up for was now over — had she re-enlisted for another six months? Or was she on her way home? When John tried to send her a cablegram in return, he was told that the lines were all tied up with messages between Germany and Russia.

The Gruels remained in suspense until February 6, when they finally received a letter from Emma dated January 10. It was the first in months, and the only reason it reached them at all was likely because it had been mailed in New York by a doctor from Emma's unit returning to the U.S. In the letter, Emma assured her parents that she was well — and not starving, as she feared they might expect from the news reports of conditions in Germany. As to when she would come home, that was still uncertain. All the doctors and nurses of her unit, except the one who'd mailed her letter, had decided to remain in Germany as long as conditions allowed.

Three days later, the Hobart News carried the report that President Woodrow Wilson had broken off diplomatic relations with Germany owing to the latter's stated intention to resume unrestricted submarine warfare. Wilson ordered the U.S. ambassador to leave Germany, and the German ambassador to the U.S. was given his passport in the expectation that he would withdraw.

The following week, the Gruels were notified by the Chicago headquarters of Emma's relief organization that the German government had ordered her unit to leave the country with the American ambassador. Close on the heels of that report came another: Emma was on her way home. Another month, and John and Louise would have their daughter back.

I expect they went about their daily routine saying silent prayers for Emma's safety, as now German submarines were added to the other hazards she faced on her voyage.

After a few days of hope and fear, a second report from the relief organization took it all back — Emma was not on her way home. The German government had relented and given her unit permission to remain in the country, or to leave, as they chose; Emma and her colleagues had chosen to remain for another six-month term.

So, for the immediate future, Emma was out of reach of the submarines and other dangers of the ocean; but with relations between Germany and the U.S. deteriorating, John and Louise still had reason to fear for their daughter.

Sources:

♦ Hobart High School Aurora Yearbook, 1918.

♦ "Local Drifts." Hobart Gazette 19 Jan. 1917; 23 Feb. 1917.

♦ "Miss Gruel Ordered to Leave Germany When Gerard Party Left." Hobart News 15 Feb. 1917.

♦ "Personal and Local Mention." Hobart News 4 Jan. 1917.

♦ "Receives Good News." Hobart Gazette 9 Feb. 1917.

♦ "Wilson Breaks With Germany." Hobart News 8 Feb. 1917.

No comments:

Post a Comment