Barbarians at the GateThere is a bitter feeling in this section against the automobilist and many are wondering what can be done to protect their lives and property. (Hobart Gazette 29 Sept. 1905)

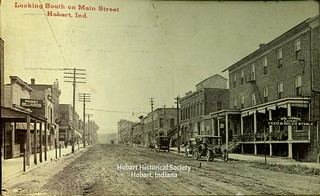

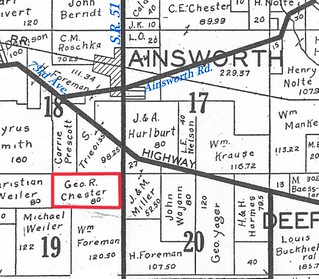

By 1904, automobiles were rolling through the Ainsworth-Hobart area in numbers great enough to create a nuisance.

The roads of the area at the time were almost as quiet as the fields. People often let their livestock roam them, confident that the animals would return undamaged. In June 1905 Trustee Alwin Wild placed a notice in the

Gazette complaining that horses, cattle, sheep and swine were daily running at large on the streets and highways of Hobart Township.

So when autos, fast and noisy, first appeared on those peaceful streets, their effect must have been jolting.

They shared the roads with the usual means of transportation, horses. Unaccustomed to the noise and speed of the machines, horses occasionally shied and bolted; wagons and buggies were damaged, their occupants frightened and sometimes injured. Now and then cars plowed right into horse-drawn vehicles. And automobile drivers, especially those who weren't local, showed an astonishing indifference to the destruction they left in their wake.

Leaving the scene of an accident may have been a breach of human decency, but it apparently was not illegal at the time. The law (as it usually does) lagged behind technology. Many of the legal duties and protections pertaining to autos that we take for granted now were absent — speed limits, lane markings, headlights, turn signals, rules of the road, insurance, drivers' licenses, license plates and registration, ticketing, and even a clear notion of when and to what extent law enforcement could act against misbehaving motorists.

Furthermore, the local roads were not equal to the demands of the auto. Many roads were still dirt; the best were only graveled, and the weight and speed of autos caused significant wear. In August of 1904, the

Gazette complained: "The fine roads through the country, built principally by the farmer for his use and pleasure, are, at this season of the year, so monopolized by the autos that the farmer can take little pleasure going out riding." Roads were paid for by levies on township citizens, while Indiana auto owners paid only a one-time registration fee of $1, and out-of-state motorists, of course, contributed nothing. It's no wonder, then, that the coming of the auto first aroused a "bitter feeling."

It also aroused confusion, and required improvisation in the absence of formal law or even established custom. For example, in May of 1904 John Sievert was driving his family home from church in a horse-drawn spring wagon when a passing auto frightened the horses, who plunged into a ditch and upset the wagon. Mrs. Sievert was injured by the fall, the horses by running into a barbed-wire fence. Obviously, there was damage, but was the driver of the auto that frightened the horses responsible for it? Someone sent for a local marshal; when he showed up, all he did was act as arbitrator between the parties. After a parley, Sievert and the auto driver agreed on $25 as damages. The driver handed over cash and went on his merry way back to Chicago, and that was the end of the matter.

That accident was remarkable in that the driver actually stopped, but unremarkable in that he was from Chicago. The

Gazette railed particularly against "those reckless city cusses who have no respect for human beings when they go thundering along the roads."

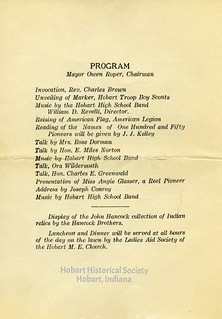

Just a few months later, two prominent Hobart citizens, Sela Smith and Owen Roper, were driving a wagon east of town when they saw an auto coming on fast. They directed their horses toward the side of the road, but couldn't get over quickly enough, and as for the car's driver, he never swerved — his car struck the back wheel of the wagon, knocked out several spokes and threw the wagon against the fence. Nor did he stop after the collision. "The auto never slackened its speed," said the

Gazette. Smith and Roper noticed that the car had a number, meaning it was probably from Chicago. Notably absent from the

Gazette was any follow-up about contacting Chicago authorities to identify the car's owner and make him pay for the damage.

The following month, a Ross Township farmer named William Halfman was driving his horse and buggy along Ridge Road when a car approached from behind at 40 to 60 m.p.h. (estimates varied). The car slammed into Halfman's outfit, cutting the horse's leg, breaking the rig's front wheel and nearly throwing man, horse and buggy into the ditch. Without even an apology, the motorist took off. About 150 yards up the road, the tire that had struck the rig blew out and finally brought the car to a halt. Halfman ran up to confront the driver, who gave his name as Williams and said he was president of the Illinois Bridge Company. Attracted by the noise, a number of farmers in the area now gathered around the scene, and Williams later said that he had been in fear of being lynched. He was allowed to leave unmolested, however, and the next day Halfman traveled up to Chicago to negotiate a settlement. Williams agreed to pay for the damaged buggy and the permanently lamed horse. He also admitted that when he fled the scene of the accident, he thought he'd killed Halfman.

Nor was the horse-auto conflict the only problem. As might be expected, alcohol and autos soon mixed. In August 1905 police in Valparaiso had to stop a car being driven by a thoroughly drunk man, with two drunk passengers (one of them an unnamed Ainsworthite). The driver was "unable to run the machine straight" and when police stopped him, he became combative, boasting that "he didn't intend to obey the city officials or anybody else." He was put in jail, then fined $20 plus costs.

In October a Minnesota motorist traveling through Hobart was stopped for speeding. What was striking about the case was the wildly varying estimates of his speed. He claimed it was only eight m.p.h., but witnesses insisted he'd been going 30. Either side may have been consciously lying; and it's possible that automotive motion was still too unfamiliar for either the driver or the onlookers to be able to estimate speed accurately; but it's also possible that the 30-m.p.h. estimate was the translation into numbers of the alarm aroused by the spectacle of a large, noisy and dangerous-looking machine arrogantly breaking through the quiet of Hobart's streets.

It Ought to Be Against the Law!

Eventually the machinery of government began to respond to the problems raised by the increasing presence of automobiles.

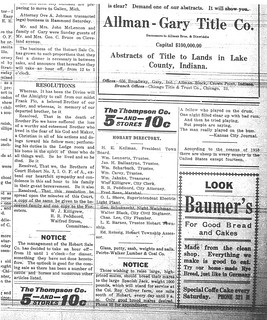

In January 1905, the

Gazette printed a letter it had received from Indiana State Senator T. Edwin Bell, acknowledging that during his campaign visits to Lake County, he had encountered "a general feeling … opposed to the reckless running of automobiles as being done today by Chicago parties" (and he hastened to assure the

Gazette that Indiana drivers were neither reckless nor careless). Without going into particulars, he promised to work for legislation that would "check this recklessness and safeguard the people."

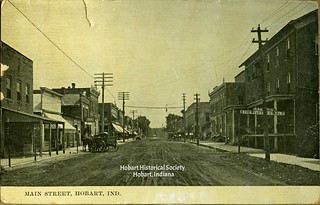

The town of Hobart had anticipated Senator Bell. In June of 1904, the town fathers enacted Ordinance No. 73 — Hobart's first speed limit. It prohibited any motorized vehicle from traveling faster than six miles per hour on Hobart's streets. To be fair, it also prohibited horses and horse-drawn vehicles from traveling "faster than an ordinary trot." The fine for speeding was $10. "Just watch Marshal Busse 'jump onto' the first auto that sails through Hobart faster than six miles an hour," gloated the

Gazette.

Senator Bell kept his word, introducing a bill that would restrict autos to four miles per hour when passing any other vehicle or turning a corner, and give road supervisors the powers of peace officers, including authority to arrest lawbreakers. Senator Daniel Crumpacker introduced another bill proposing statewide speed limits for urban and rural areas. Over a dozen auto-related bills were introduced at that session of the Indiana legislature, proposing such things as registration of and license plates for cars, licensing of chauffeurs, a code of signals to be used among motorists and other drivers, and placement of signposts to guide drivers.

The bill that ultimately was primarily Senator Crumpacker's version. Governor James Hanly signed it into law in March 1905. It established statewide speed limits of eight miles per hour in "closely-built-up" municipal areas, 15 m.p.h. in other areas of towns, and 20 m.p.h. outside cities and towns. It required a motorist to stop his car if signaled to do so by the driver of a horse, but also imposed on both motorists and horse-drivers the duty to give up half the road whenever one passed the other. And finally, it mandated the registration of motor vehicles with the Secretary of State.

Early in June the Indiana Supreme Court decided that a motorist could be held liable for damages resulting from an accident caused when his vehicle frightened a horse. The

Gazette summed up the ruling: "[W]hile automobiles have a right to use the public roads they must act with due regard for the rights of others."

But What Is the Law?

In spite of governmental efforts to impose order on the automobile-generated chaos, within a few years a spectacular dust-up in Hobart between motorists and law enforcement personnel showed how unsettled the state of automotive law still was.

It began on a Friday afternoon in mid-July, when two chauffeur-driven cars sailed through the town of Porter, Indiana. One was from New York, carrying E.S. Giverson, President of the Bedford Quarries Co., and his party; the other, from Illinois, carried A.E. Dickinson, Vice President of the same company, along with his party — altogether, five men and four women, on their way to Chicago.

Marshal Busse, seeing that the two cars were breaking the six-mile-per-hour speed limit, hailed them to stop. They ignored him. In fact, they almost ran him down in the road as they continued west. Busse telephoned to Hobart, asking Marshal Fred Rose to stop the two cars if they showed up there.

So when Marshal Rose and Deputy Sheriff John Green saw two out-of-state cars parked near the Hobart post office, they went to investigate. The men of the party had stepped into The Hub to refresh themselves; as the women waiting in the cars spoke among themselves, Rose overheard a remark that convinced him these were the two cars Marshal Busse wanted.

He stepped up to the Illinois car, while Green stepped up to the New York car. The men of the auto party came out of The Hub, and Rose politely informed them that they were being detained for speeding in Porter. Dickinson, owner of the Illinois car, told his driver not to resist, but the New York chauffeur — a Princeton University student named W.B. Bolmer — threw a punch at Green. He dodged it, and in doing so stumbled over the tongue of a reaper standing nearby. Rose at once stepped to the New York car and ordered Bolmer to stay where he was. Ignoring him, Bolmer revved his engine. Rose jumped onto the side of the car. Then Bolmer fetched Rose a "terrific backhanded blow upon [his] face and right eye," stepped on the gas and took off down the street, with Rose still clinging to the side of the car. The fight was on, with Rose trying to hang on and Bolmer trying to push him off, while the women in the back seat scratched and slapped the Marshal and pulled his hair.

The car rolled down the street, with several men and boys who had gathered around now pursuing it on foot. Someone yelled ahead for help to a small group standing on the Third Street bridge. One of them, "Butch" Klausen, grabbed a length of gas pipe and ran out into the road ready to wield his weapon. At that point Bolmer finally stopped the car. Rose pulled him out and marched him off to the jail.

(The

Gazette recorded that one of the women in the car was nearly hysterical in her verbal abuse of all Hoosiers, calling them all sorts of names, the most printable being "hogs," and lamenting her shame that her own mother had once lived in Indiana.)

After Marshal Rose had gotten medical treatment for his eye and all the parties had cooled off a little, they met at the home of the justice of the peace, with their respective attorneys. Rose was offered $200 to settle the matter, but he refused it. Bolmer stayed in jail overnight, while the other driver, who hadn't resisted, was taken back to Porter, pled guilty to speeding and paid the minimum fine. When Bolmer was released on bond the following day, he too was spirited off to Porter and fined for speeding.

The fracas itself was not as surprising as the verdicts in the legal cases that followed.

Rose immediately filed three lawsuits against Bolmer: for assault and battery; for resisting an officer; and for personal damages. Green also filed a suit against Bolmer for assault.

The first two of Rose's cases were tried in a Gary court before the end of the month. Rose, his attorneys, the editor of the

Gazette and probably many Hobartites were stunned when the jury took a mere thirty seconds' deliberation to return a verdict for the defendant. "It appears from this case," the

Gazette said, "that an officer is practically helpless when it comes for enforcing" speed limits. "All an auto driver has to do is to put on more power, dodge the officer, wear a broad grin and skip."

Two days later, Green's assault case against Bolmer was tried in a Merrillville court. Green won; Bolmer appealed; in October the Lake County Superior Court found for Bolmer.

The next day, Rose's third lawsuit — for personal damages — was tried. The judge found in favor of the defendant. Rose appealed. When his appeal was finally heard in April 1910, the judge, after hearing the evidence, ruled that "the act committed [by Bolmer] was not sufficient to permit the arrest without a warrant," directing the jury to return a verdict for the defendant.

The

Gazette commented that Marshal Rose "was acting in good faith when he arrested them and was basely assaulted by Chauffeur Bolmer, for which he seems to have no redress under the law."

A few months later, an Illinois car struck a horse-drawn wagon driven by a Hobart boy, damaging the wagon. The car did not stop. The boy, who had escaped injury, had the presence of mind to note the car's license plate number, and when he got home his parents phoned Marshal Rose to ask him to stop the car if it came through Hobart. Rose wasn't able to find the car in Hobart that day, nor could he track it down in Chicago the next day. "Suppose the Marshal had located the machine," the

Gazette added, "what could he have done in the face of the recent decision [in the Bolmer cases]?"

We Have Met the Enemy, and He Is Us

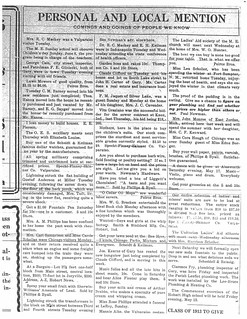

Cars continued to speed, no doubt, and to confound law enforcement, crash into buggies, frighten pedestrians and tear up the roads; but after 1905, the

Gazette ceased its bitter invective against them. Its softened attitude can be explained by the automotive fever that had caught hold among its own readership. The same Ross Township farmers who, in 1904, had spoken of organizing an anti-automobile club were beginning to buy their own automobiles.

In August 1906 the

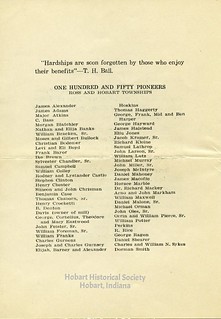

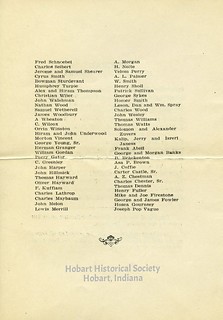

Gazette announced that Hobart now boasted seven autos. Fred Hamann became the town's Ford agent; by 1910 he was doing a land-office business, and his customers included many from Ainsworth and Ross Township — some of them descendants of the old pioneering farmers. Charles, Jim and John Chester bought Fords from Fred; so did William Wollenberg, William Raschka, John Gruel, Earl Blachly and John Harms. So too did William Wood, the Deep River merchant descended from the town's founding family, and William Waldeck, Deep River's blacksmith. In March 1911, Hamann reported that he had sold 14 Fords already that year. By August he had sold 21.

Now the social columns were peppered with auto-related joys and sorrows. John Sturtevant took a lady friend out motoring. Rudolph Wojahn boasted of traveling at 45 m.p.h. on his brother's motorcycle. A car going about 40 m.p.h. ran over one of Mike Foreman's pigs (the driver didn't stop). Walter Blachly bought an E.M.F. auto. Thomas Sullivan bought an Overland. William Raschka drove his new Ford into his "garage room" too fast, damaging a door and lamp on the car. Clarence Dorman bought a Badger and his father drove it home, 200 miles, from the factory in Wisconsin. Even the lesser excursions of other locals rated a mention — to Hobart, to Valparaiso, to Michigan City and LaPorte. One column dryly noted: "Ainsworth needs a number of speed limit signs for autos"; another reported that John Chester and E.D. Scroggins had driven to Elgin, Illinois, to see an auto race.

By 1911 a few Ross Township farmers (current or former) even turned to selling cars. Hubert Bullock sold Abbott-Detroits, and among his customers were fellow farmers Fred Schnabel and William Lute. The Dorman brothers sold Badgers — among others, to E.D. Scroggins (who, as we've

seen, used his new car to establish an auto livery service), and to John and Charles Chester, who apparently had already grown tired of their Fords.

In June of that year the

Gazette reported on a grand auto excursion organized by John F. Dorman. Ten cars carried such prominent locals as Hubert Bullock, E.D. Scroggins, Judd Blachly, William Raschka, Charles Goodrich, William Wollenberg, John Chester, Scott Burge and C.F. Frailey. With their families and friends, the whole party numbered about fifty. They drove to South Chicago, where John Dorman's brothers, Charles and William, joined the party in their own cars and "piloted the Hoosiers through the various parks of the city." After a lunch in Lincoln Park, the party returned home delighted with the day's outing.

Within a couple months, C.F. Frailey sold his horse livery behind the Hobart House, but he continued to operate his auto livery service. Edward Rohwedder, after buying his father's horse livery, added a Ford to his stable.

Gust Wojahn drove that fast motorcycle of his home from Chicago in only one hour and 34 seconds. Impressed, Lawrence Smithers bought his own motorcycle.

Hubert Bullock abandoned farming altogether and moved to Valparaiso to repair and sell cars.

Conflicts continued, but the war was over, and the surrender enthusiastic. For better or for worse, the farmers and blacksmiths, the merchants and saloonkeepers embraced the automobile. In August of 1911, the

Gazette quoted John Harms, whose family had been farming in Ross Township for at least three decades, and whose declaration of newfound love no doubt voiced the feelings of many of his neighbors: "There is nothing in life without an auto."

Sources