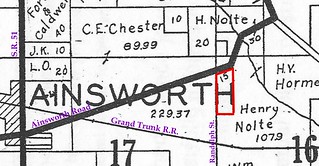

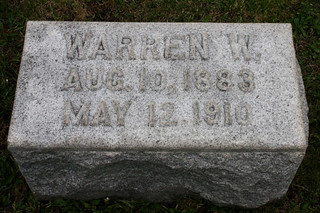

I'd like to take a vacation from all this death and misery (which isn't over yet, by the way — 1910 was a bad year for anyone with an Ainsworth connection), and just for a little while I'd like to get out of Ainsworth. So if the neighbors will hitch up their horse and buggy and drive us to the depot, let's catch the train and travel to southern-central Illinois.

This story takes place in the triangle formed by Litchfield, Butler and Hillsboro, Illinois, three small towns about 50 miles south of Springfield. During the closing years of the 19th century, this area was graced by a new resident — a young man named Ellis Glenn. No one knew where he came from, no one knew his family, but in spite of his lack of pedigree, he soon won a place in the best small-town society with his charming personality, youthful good looks, and dapper appearance. All the village belles were smitten.

Ellis got a job as a sewing-machine salesman, which required him to travel around the area. During a business trip to Butler in the spring of 1899, he took lodgings in the home of a wealthy local farmer, James Duke. James had two daughters at home. Ellis began courting the younger one, Ella, and she fell for him, hard.

In April, a couple of farmers living near Hillsboro claimed that Ellis had forged their names to a $4,000 note that he used to buy some Litchfield property. Ellis was charged with the crime, but James Duke put up the bond so that his daughter's sweetheart could come back to the Duke household.

The wedding was set for October 18. On October 16, Ellis vanished.

A couple days later, Ella's sister received a letter from St. Louis, signed by a stranger, one T.H. Perry. The letter carried the sad news that Perry's good friend, Ellis Glenn, had drowned there.

Law enforcement officials weren't buying it, and sure enough, just a few days later they caught up with Ellis in Paducah, Kentucky. They brought him back to Litchfield to stand trial for the forgery. He was convicted and sentenced to a prison term.

On arrival at the penitentiary, he underwent the usual admittance procedures. His hair was shorn; his photograph was taken; then he was ordered to discard his stylish clothes, take a bath and put on the prison uniform. He did so — or, at least, began to do so, for as soon as he took off his clothes to step into the bathtub, it became obvious that "he" was a woman.

There must have been embarrassment all around. As one newspaper report put it, "She was promptly hustled into her clothes."

And oh, what a story she had to tell. No, she was not Ellis Glenn, of course: she was his

identical twin sister. She had met him in Paducah, heard the sad tale of the forgery charge he was running from, and decided to take his place, donning men's clothing and letting herself be caught by detectives, so that she could return to Litchfield and be convicted of the crime, thus saving her brother from the horrors of prison. She refused to tell anyone her real name or where her brother was.

Nobody believed her, of course.

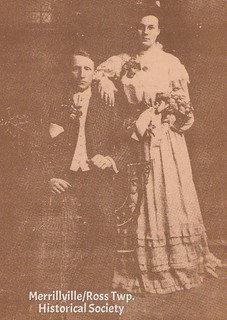

Ella Duke had been completely unaware that her fiancé was a fiancée. She and her father visited Ellis in prison, where "the three held a long interview. They wept long and loud and the lovers embraced each other with great fervor." Heartbroken and confused, Ella refused to believe that Ellis was anyone other than her own sweetheart, certainly not a twin sister — certainly not a woman. One newspaper said that Ella still loved Ellis and would "stand by her to the end."

No one was quite sure what to do with Ellis, and a motion to quash her indictment was being argued when someone showed up who knew exactly what he wanted done with her: William Richardson of Parkersburg, West Virginia, came, saw, and identified Ellis as the same "E.R. Glenn" who had defrauded him of $1,000 back in West Virginia several years ago — already masquerading as a man even then. He wanted Ellis taken back east to stand trial for that crime.

Illinois seemed glad to get rid of her. She was taken back to West Virginia, where after standing trial and being acquitted, she was free to go about masquerading as whatever she pleased. I don't know what became of her after that.

I don't know what became of Ella Duke, either. I hope she recovered from her broken heart. She had plenty of opportunities to console herself: since her picture had appeared in the papers in connection with the case, Ella had been besieged by men all across the country wanting to correspond with her. And a local suitor, whom she had discarded when Ellis caught her fancy, renewed his attentions.

Sources:

♦ "A Woman-Man." Alton Evening Telegraph (Alton, Ill.) 27 Nov. 1899.

♦ "An Ardent Lover Proves to be a Female — Her Story." Hobart Gazette 1 Dec. 1899.

♦ "Changes Sex." Daily Review (Decatur, Ill.) 27 Nov. 1899.

♦ "Ellis Glenn Acquitted." Free Press 17 Mar. 1900.

♦ "Identified." Daily Review (Decatur, Ill.) 9 Dec. 1899.

Well, that was fun, but vacation is over.