His Brilliant Career

Michael Carrozzo

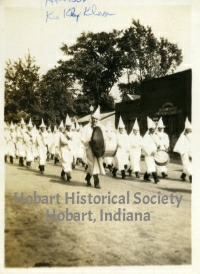

Image courtesy of the Hobart Historical Society.

After Carrozzo's his death the press would say, "His rise to wealth and power was almost as quiet as it was fabulous and few could tell how he achieved them." Even today, information about him turns up as a few lines in biographies of more notorious men, or in histories of vice operations and labor racketeering in Chicago. And the details in those lines tend to vary from source to source. As one unfamiliar with the history of labor unions and organized crime in early-twentieth-century Chicago, I could only do my best to tease out, from all those varying sources, a sketch of Carrozzo's quiet and fabulous rise.

He was born in Montaguto, Italy, in 1895, and immigrated to the United States at about eleven years of age. By 1910 he had come to Chicago, settling in the Italian neighborhood and working as a street-corner shoeshine boy in Levee district of the First Ward.

At that time, the Levee was Chicago's capital of vice and corruption. There one could find the city's most spectacular brothels, alongside saloons and gambling dens. There reigned two of its most notoriously corrupt aldermen, "Bathhouse" John Coughlin and Michael "Hinky-Dink" Kenna. And there "Big Jim" Colosimo was beginning to build an empire.

Colosimo's genius seemed to lie in organization. He has been called a pioneer in the field of labor racketeering. He started out as a streetsweeper, a dirty job in those days before the auto replaced the horse. He began working to organize his fellow streetsweepers into a voting block, which he controlled. At the same time, he was involved in gambling operations. His career got another boost when he married Victoria Moresco, the madam of a whorehouse; she taught him the business of running a brothel. He would eventually own or control about 200 of them.

Colosimo noticed the young Carrozzo, decided the kid had potential and got him a job as a streetsweeper — a "white wing," as the sweepers were called in honor of their white uniforms. The young Carrozzo quickly won his mentor's good opinion by helping to organize and control the streetsweeper votes. Along with Tony D'Andrea, Carrozzo worked to consolidate Colosimo's control by organizing the Italian community into a voting block, and was rewarded with an appointment as a precinct captain.

Apparently Carrozzo became one of Big Jim's trusted assistants, although it isn't clear exactly what his role was outside of the labor-union organization. According to some sources, he was Colosimo's personal bodyguard. Another source depicts Carrozzo and the young newcomer, Al Capone, guarding the alley behind Colosimo's Café. Others describe him as a sort of personnel manager or talent scout for Colosimo's line of brothels.

Whatever he did, his boss was grateful, and rewarded him well. In 1919, Colosimo got Carrozzo appointed president of the streetsweepers' union. This position meant both power and profit, for the union leaders skimmed off as much as half the memberships' dues.

Left to right: "Big Jim" Colosimo; his father, Luigi; and his successor, Johnny Torrio.

In 1920 Prohibition went into effect and opened up a new field of enterprise for organized crime. Eager to enter that field was an ambitious assistant of Colosimo's — Johnny Torrio, a relative brought in from New York by Big Jim to do some of his dirty work. But Colosimo himself wasn't interested in bootlegging. He had become infatuated with a young singer in his nightclub; early in 1920 he divorced Victoria in order to marry the songstress, and his enthusiasm for his own business seemed to slacken. Torrio lost patience with his boss. In May of 1920, the newlywed Colosimo was assassinated in his own nightclub. Some 30 suspects were questioned — Al Capone among them — but the case was never solved.

Mike Carrozzo remained in Torrio's good favor.

Torrio split Colosimo's empire unevenly with Capone. While continuing their inherited vice operations and labor racketeering, they also developed an impressive bootlegging organization. In the mid-1920s, probably in fear of Capone's growing ambition, Torrio wisely retired to New York. By the end of the decade, Capone was the king of organized crime in the Chicago area.

Al Capone

Carrozzo retained Capone's good opinion. He also retained and expanded his own union control. When "Diamond Joe" Esposito died in 1928, Carrozzo inherited his presidency of the Hod Carriers' International Union and his seat on the executive board of the AFL. He now controlled at least 25 Chicago unions. He also controlled Chicago's public paving projects, taking a five percent cut of every paving contract.

Carrozzo's relationship with the unions was not solely to his benefit. For example, in 1925, after a week-long strike, he won pay increases for streetsweepers (up $.50 a day), street repair workers (up $1.00 a day), and garbage dump foremen (up $35 a month).

In 1931, Al Capone was convicted of tax evasion and sentenced to 11 years in prison. He appointed his own successor, and Frank "the Enforcer" Nitti became Carrozzo's new boss.

Frank "the Enforcer" Nitti

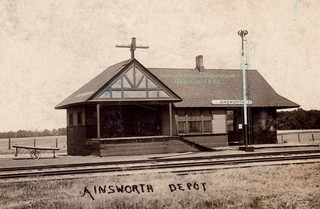

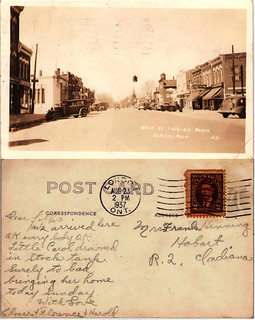

By the mid-1930s Carrozzo's life was going well. He was rich. He was married, with two young children. Out in the peaceful environs of Ainsworth, the Gruels' flourishing dairy business attracted his attention. It looked like a good investment. And Ainsworth looked like a nice place to spend some time.

The Country Squire's Estate

Carrozzo already owned an elegant second home in Long Beach, Indiana, called the "Villa C." His Ainsworth estate would be on a grander scale. His first purchase was just the Gruel family's land, but soon he bought up adjoining farms until his holdings comprised 900 acres and spilled over into Porter County.

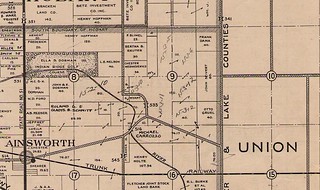

(Click on image to enlarge)

The 1939 plat map above shows the extensive Carrozzo holdings. On this map, bought at auction on land that had once been Carrozzo's, someone has outlined in pencil the boundaries of his property, as well as noting some of the parcel numbers.

The farm's change of ownership happened quietly. The Vidette-Messenger carried just a few lines to the effect that the dairy was being bought as an investment, with not a word to suggest that "M. Carrozzo, of Chicago," was anyone out of the ordinary. The Superior farm continued to operate as usual; in fact, four of the Gruel brothers stayed on to manage it under its new ownership.

But as Carrozzo bought up more acres and spent impressive sums — reportedly $40,000 — to improve and beautify the property, the farm became a playground and began to attract local attention. A year after the sale, the Vidette-Messenger had a good deal more to say about the farm and its new owner — and about the overly dramatic reportage of the Chicago Tribune:

Farm In Hobart To Be New Haven For Al Capone?The "stable of horses" contained prize-winning thoroughbreds; Carrozzo's wife, Julie, bred and trained them.

Farmers in this small agricultural community … speculated today about the recent sale of a vast, normally equipped farm.

Squire of the huge estate is said to be Michael Carrozzo, head of the street laborers' union in Chicago. The telephone is listed in his name.

The Chicago Tribune said one report was that the farm would be a hangout for Al (Scarface) Capone when the one-time Chicago gangster chieftain completes a year's term in Cook county jail after his release from Alcatraz penitentiary next January.

Neighboring farmers could neither confirm nor deny the report. … All they knew, they said, was that operations were being conducted there as on any other farm — about 150 blooded milk cows were grazing in the pastures and their milk was being marketed.

The Tribune said that whenever Carrozzo goes on the huge estate "he is within sight of a number of hard faced, chunky little men" and that "neighbors have learned that each of the 'secretaries' carries a large bore pistol on his hip."

A Gary newspaperman, on a visit to the farm today, said the men he saw "looked like farmers" and that he could not detect any gun toting. Some of the men, he said, were engaged in routine farm work and others were engaged in renovation.

The Tribune said Carrozzo appeared at the home of one farmer and bought a 320-acre tract with 145 $1,000 bills and subsequently purchased four adjoining farms, bringing his holdings to 900 acres.

The newspaperman said he learned the transaction was handled through a nearby Gary real estate firm, that payment was by check….

According to the Tribune, the gateway to the farm is blocked by heavy iron barriers. The Gary newsman said he found the gates open and visited the farm, finding scores of blooded cattle, large barns, a stable of horses and an exercise track. He said neighboring farmers believed the farm was being operated as such and that they were inclined to doubt the report that Capone eventually would make it his hangout.

Efforts to locate Carrozzo here or in Chicago for comment were fruitless.

Sources close to the old Capone gang in Chicago doubted the report. They believed Capone would go to his home at Miami, Fla.

Despite the anonymous Gary newsman's debunking, the rumor that Carrozzo had paid cash for his new estate took root and was still being reported years later.

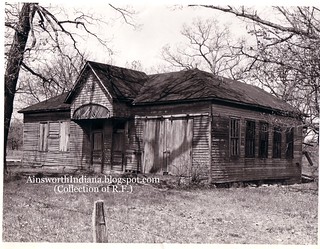

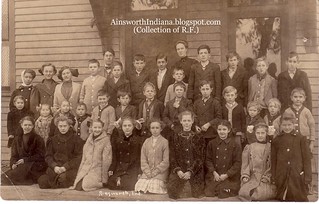

Above and below: House and outbuildings at the Superior farm. (Photos courtesy of the River Pointe Country Club.)

(Click on image to enlarge)

Aerial view (1939) of a small part of the Carrozzo land, north of Ainsworth Road and west of the county line (which is at the right border of the photo). The complex of buildings at the upper left included the house and the dairy outbuildings. The oval at the lower right may be the exercise track mentioned in the newspaper article quoted above.

In addition to the thoroughbreds, there were Hereford cattle and draft horses. Even the Carrozzo pigs won prizes.

The absence of the Carrozzo name from the social columns of the local papers — which reported such events as one family's dining at another's house, or an outing to an area park — suggests that the Carrozzos did not mix socially with the local people to any great extent, although they did contribute to the area economy by hiring numerous locals for farm and house work. Stories about them persisted in the neighborhood for years; a lifelong Ainsworth resident recalls hearing as a child about the Bantam Roadsters in which the Carrozzo children used to race around the farm, and about the machine-gun turrets atop the barns — the latter being, no doubt, tall tales the neighborhood kids told each other for thrills.

Life on the country estate seems to have been peaceful if not strictly virtuous. A Hobart woman once employed there reminisced to the Post-Tribune half a century later about her experiences chez Carrozzo. Sometimes there were heavy bouts of gambling; in their aftermath, she said, "I would shuffle the money in bushel baskets." She remembered once taking a phone call from Al Capone in prison. She added, "You weren't allowed to answer the door. You weren't allowed to give out information. But they were all perfect gentlemen to me."

Two Things in Life Are Inevitable

One day in May of 1939, three federal agents left the U.S. courthouse in the Chicago Loop, walked a block over to the First National Bank, and there seized Mike Carrozzo's bank vault. They were convinced he owed the government income tax — a whole lot of it. A lien of over $200,000 would follow, with the possibility of criminal charges still to come.

According to the Hobart Gazette, it was the purchase of those 900 acres of prime Indiana farmland that first made federal authorities curious about Carrozzo's true income. In 1937 and 1938, his declared income was about $12,000 — a respectable sum, but just upper-middle-class. And yet there was the sprawling Ainsworth estate, the lavish house, the barns full of first-class dairy cows, the stable full of thoroughbred horses, in addition to the elegant Long Beach home. And there was Carrozzo's "sumptuous" Chicago office, where a sign on the wall listed just some of the unions he controlled.

The feds were hoping to replay their success in the case of Al Capone: suspected of criminal acts up to and including murder, Capone always eluded conviction until at last a charge of tax evasion put him behind bars. Carrozzo likewise had been suspected of many things, including several murders — of "Mossy" Enright in 1920, of Dion O'Banion in 1924, and of "Big Tim" Murphy in 1928. But he was still a free man.

And so the feds concentrated on his lesser crimes. They spent the rest of 1939 and the first half of 1940 building their cases.

On June 24, 1940, a federal grand jury indicted Carrozzo and nine others on charges of labor racketeering, including violations of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act by conspiring to prevent the use of ready-mixed concrete in Chicago construction projects. A month later, an internal revenue collector slapped a $241,088 lien on Carrozzo's assets for alleged unpaid income taxes plus interest and penalties. Carrozzo went to the federal courthouse and posted $277,351 in bonds to lift the lien.

On July 27, Carrozzo, who suffered from kidney disease, became so ill that his family had him rushed to Presbyterian Hospital in Chicago. He underwent surgery on August 2. The next morning his doctor was pleased to find him recovering nicely, but later that day he suffered a relapse and by nightfall had lost consciousness.

On Sunday morning, August 4, 1940, Michael Carrozzo died in his hospital bed, peacefully, of natural causes.

The Aftermath

Carrozzo left behind his widow, Julie, and two children: eleven-year-old Michael George and eight-year-old Carole Ann. Julie was appointed administratrix of his estate and granted a $1,200 monthly fee to manage the Ainsworth farm.

At the time of his death Carrozzo was reported to be a millionaire. A few weeks later, reports had come down to an estimated half-million-dollar estate.

Out of the shadows of the past and into the light of the Cook County Circuit Court came Mary Carrozzo — the first Mrs. Carrozzo — demanding a share in that estate. She claimed that Mike had married her in 1911, then bigamously wed another woman in 1919; for that reason, as well as a technicality involving the service of process, her 1921 divorce from Mike had been invalid. Mary's contention was that Mike's marriage to Julie, which occurred after 1924, was bigamous and invalid, and that she, Mary, was legally his wife and the heir to the $500,000 estate.

But the estate, when the will was filed, was estimated at only $30,000 in personal property and $165,000 in real property.

Julie Carrozzo's legal counsel was the Chicago firm of Gottlieb & Schwartz. They administered the estate and successfully defended it against Mary Carrozzo's suit, as well as suits by three labor unions Carrozzo had run. They also negotiated a deal with the government whereby Carrozzo's disputed income was spread over six years instead of three, greatly reducing the delinquent amount. In April 1943 Gottlieb & Schwartz sued the estate for $57,000 worth of legal work and eventually settled for a payment of $20,000.

On May 11, 1943, Julie Carrozzo sold the Superior farm to Dr. Walter M. and Frieda Behn, of Gary, and those gently rolling acres rolled back into prosperous obscurity.

Sources