Jeremiah Wiggins, the first white immigrant to settle in Ross Township,[2] passed through the early history of the area that eventually became Merrillville without leaving much evidence. He lived there, but he was never recorded in a census. He farmed there, but his name never appears on a plat map. He died there, but his grave is unmarked, its exact location unknown. He left behind no family to preserve his memory.

Writing 66 years after Jeremiah's death, the Rev. T.H. Ball said of him: "He seems to have been a lone man without much connection with any one."[3] A 1915 history cited the Rev. Ball's assessment and added:

Jeremiah Wiggins appears to have been one of those mysterious men who are ever wandering into new communities, who come from out of the shadow of Somewhere and merge into the shade of Nowhere. The Claim Register does not record him, although most of the pioneers agree that he appeared at the site of the Indian village some time in 1836.[4]In 1956 a former Post-Tribune editor, Harold Van Dusen,[5] wrote an article for that paper in which he embroidered upon some stories about Jeremiah that I have found in a plainer form in earlier histories.[6] Unfortunately, Van Dusen cites no sources, so I don't know whether the threads of his embroidery were spun only from his own imagination. And in light of the fact that he consistently gives Jeremiah's surname as Higgins, I am not sure how reliable the article is.

According to Van Dusen, Jeremiah, "big, brawny, bearded," came into Ross Township in March of 1835 and stopped at the Native American crossroads known as McGwinn's Village, which included a ceremonial dancing area and a large burying ground with as many as a hundred Native American graves. Jeremiah was able to speak with the local Potawatomi people in their own language, and he had a persuasive manner. He allayed their suspicions by trading with them and offering to let them use some of the land he would plow up to grow their own crops. He settled there, built a cabin, and began farming.

Incidentally, Van Dusen does not give details about the exact location of Jeremiah's claim, but other sources seem to point to the southeast corner of the intersection of what is now E. 73rd Avenue and Broadway. A Standard History of Lake County tells us that the Wiggins land soon passed into the hands of Ebenezer Saxton,[7] and that later Dudley and William Merrill "secured land on the north side of the old Indian trail [i.e., the Sauk Trail, now 73rd Avenue], opposite the Wiggins-Saxton claim."[8] The (1874 Plat Map) shows Saxton and Merrill land lying on opposite sides of 73rd:

(Click on image to enlarge)

Assuming that the Saxton and Merrill land had not passed out of those families' hands in the thirty-some years between their first arrival and the making of the map, this locality seems to match the description.

But let's get back to Van Dusen: he tells us that Jeremiah's friendly relations with the Potawatomi did not last.

The trouble started one morning when a fresh grave in the Native American cemetery was found to have been opened and the body in it stolen. Potawatomi searchers traced wagon tracks past the cemetery northward to the coach road to Michigan City, and concluded that the desecration was done by a passing traveler, who would never be identified for certain. So they had no specific target at which they could direct their hurt and anger. Van Dusen says:

A few days after the grave robbery two Indian braves, threateningly armed with rifles, walking into the field where Higgins [sic] was at work alone. They … walked to the open grave, not far distant, sat there with their rifles, looking across the field at Higgins every few moments.The men eventually left without violence, but Jeremiah went nuclear: he filled in the opened grave and then "used his breaking plow to turn the sod of the entire cemetery, making it a part of his field," allegedly "in the hope that he could get the villagers to forget their burying grounds."

I have a hard time believing that Jeremiah seriously expected this action to make the Native people living in the area "forget their burying grounds." The earlier source of this story (Howat, 1915) doesn't try to explain Jeremiah's motive.

The Potawatomi were, of course, deeply grieved at this mass desecration of sacred ground. They did not react violently, but they did not forget, and word of the event spread. Both Van Dusen and Howat describe an incident in 1840 — after Jeremiah's death — when 1,100 Potawatomi from Michigan, being "relocated" westward by the U.S. Army, stopped for the night at McGwinn's Village; even these Michigan residents knew where the burying ground was, and many of them sought it out and mourned over what had been done to it.

Nearly half a century after these events, a book on local history noted that this "burial-ground may still be traced on the old Saxton place."[9]

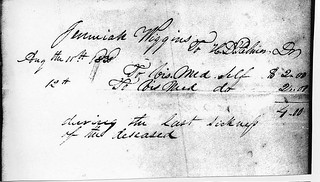

For all his "brawn" and his brazenness, Jeremiah died in his bed. He fell ill during the summer of 1838, probably early in August, and died on or shortly after August 12. We know this because Dr. Henry D. Palmer, the first formally trained physician to practice in Lake County, submitted a bill to Jeremiah's estate for medical services "during the last sickness of the deceased":

(Click on image to enlarge)

Image courtesy of Alice Flora Smedstad.

Jeremiah's was the first estate to be probated in Lake County.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Image courtesy of Alice Flora Smedstad.

Amazingly, documents from the handling of this estate survived on microfilm. Looking through them, we can see that while Jeremiah may have had no close emotional relations, he had business relations. The names that crop up give us a glimpse of some of the people who were here in the mid-1830s and a bit of what they were doing. The estate papers also let us peek inside Jeremiah's cabin.

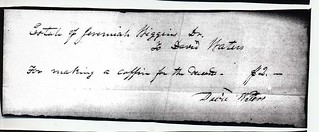

Jeremiah's fellow white settlers gave him a decent burial, apparently ("near the old Indian cemetery," according to Van Dusen). His coffin was built by David Waters, who was recorded in the 1840 Census in a household that included two small children and two teenagers, as well as two adults, in equal numbers of male and female — so we can gather he was a family man. Beyond 1840 I cannot trace him.

The coffin cost Jeremiah's estate $2.00.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Image courtesy of Alice Flora Smedstad.

I suppose it's some sort of poetic justice that the man who desecrated the graves of others should himself lie in an unmarked grave, where no one can come to pay respects, where no one celebrating the 50th anniversary, this year, of Merrillville's incorporation may place flowers. But then again, Jeremiah doesn't seem the sort of man to care much for anyone's respects or flowers.

_______________

[1] Alice was kind enough to share with me some material she had unearthed (some of which I would never have found on my own), but all transcriptions, commentary, conclusions, and mistakes are mine.

[2] Weston A. Goodspeed and Charles Blanchard (eds.). Counties of Porter and Lake Indiana. Historical and Biographical. Illustrated. Chicago: F.A. Battey & Co., 1882, at p. 544.

[3] T.H. Ball, Encyclopedia of Genealogy and Biography of Lake County, Indiana, with a Compendium of History 1834 – 1904 (Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1904), at p. 124.

[4] William Frederick Howat, M.D. (ed.). A Standard History of Lake County, Indiana and the Calumet Region. Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1915, at p. 183.

[5] Harold Van Dusen, "When Merrillville Was McGwinn's Village," The Gary Post-Tribune, Jan. 8, 1956. A note above the byline reads:

Harold Van Dusen is a former telegraph editor of The Gary Post-Tribune, serving in that capacity during World War II. He was editor of the national Purple Heart publication at that time, having been wounded while serving in France in World War I. He now is on the news staff of the Corning Leader, Corning, N.Y.He was born circa 1895 (records giving his age are inconsistent) in North Dakota, and I believe he is buried in New York. He appears in the 1940 Census living in Gary with his wife, Helen, and son, Alan, employed as an "assistant editor" on an unnamed "daily paper."

[6] E.g., Ball (1904) at 138; Howat (1915) at 41 and 96.

[7] P. 253.

[8] P. 54.

[9] Goodspeed and Blanchard (1882) at 547.

2 comments:

I kept picturing Grizzly Adams as I read this.

Yeah, maybe he liked animals better than he liked humans.

Post a Comment