(Click on image to enlarge)

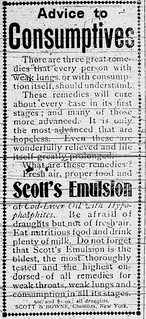

An 1898 advertisement for a quack tuberculosis remedy, from the Hobart Gazette.

I've been paying particular attention to tuberculosis since I came across stories from 1908 about the new governmental anti-tuberculosis regulations that had dairy farmers around Ainsworth in an uproar. Since I live in a time and a place where I'm very unlikely to get tuberculosis, it's hard for me to get a feeling for how real and threatening it was to my neighbors a century ago.

In 2005, tuberculosis caused just 0.2 deaths per 100,000 people in the United States. In 1900, it caused 194.4 deaths per 100,000 — only slightly fewer than influenza and pneumonia combined — while major cardiovascular disease caused 345.2 deaths per 100,000, and cancer 64.0. In 1904, nearly five thousand people in Indiana died of tuberculosis.

On the personal level, we've already seen how it devastated the Nolte family. In 1901 the Gazette reported on a Hobart family profoundly affected by it: Mr. and Mrs. J.P. Johnson, both infected with TB, had become so ill and weak that their 13-year-old daughter had to take on full responsibility for the care of her four little sisters, the youngest being only a few weeks old.

Other local deaths from tuberculosis:

- Charles Niles, 30, died at his home in Deep River on May 30, 1900. Funeral services had to be held in the house because his wife was too weak to go to the church.

- In September 1900 a 32-year-old railroad employee, David Hartland — working in spite of his tuberculosis — collapsed on the job near Deep River and died the same day.

- In Lake Station, Miss Jennie Ringberg died in 1902 at the age of 21.

- Also in 1902, Randolph Guernsey, who had gone to Colorado to try for a cure, died there at the age of 29, leaving a wife and two sons.

- In 1905, Mrs. Amanda Bullock died at age 23.

By the early twentieth century, the bacterium that causes tuberculosis had been identified, and with the new X-ray technology doctors could better diagnose the disease and track its progress in a patient; but there was no medical cure. TB sufferers were advised to get plenty of rest, fresh air and good nutrition, and to the extent such treatment strengthened the body's own immune system it could help in fighting off the infection. There were many sanatoria that offered this treatment (with the added benefit to the general population of isolating infected people), but patients had to be able to bear the financial burden involved — not only the fees charged by the sanatorium, but also the loss of work during the patient's stay there, which often stretched into months or even years. It was not until 1944, when the antibiotic streptomycin became available for use in humans, that doctors could actively cure tuberculosis.

Sources:

♦ "A Sorrowful Sight." Hobart Gazette 24 May 1901.

♦ "Advice to Consumptives" (advertisement). Hobart Gazette 9 December 1898.

♦ Dunne, Mike. "Former TB sanatorium in Placer County awash in poignant history." Sacramento Bee 7 Jan. 2010. http://www.sacbee.com/2010/01/07/2442723/former-tb-sanatorium-in-placer.html (accessed 13 March 2010).

♦ "General News Items." Hobart Gazette. 27 Jan. 1905.

♦ "Late Pick-Ups." Hobart Gazette 28 Feb. 1902.

♦ "Local Drifts." Hobart Gazette 28 Sept. 1900.

♦ "Mortuary Record." Hobart Gazette 1 June 1900; 21 March 1902; 3 March 1905.

♦ Pearson Education, Inc. "Death Rates by Cause of Death, 1900–2005." Infoplease 2007 (abstracting U.S. Public Health Service, Vital Statistics of the United States, annual, Vol. I and Vol II). http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0922292.html (accessed 12 March 2010).

♦ University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey. Brief History of Tuberculosis. July 23, 1996. http://www.umdnj.edu/~ntbcweb/history.htm (access 13 March 2010).

No comments:

Post a Comment